Painting meets found objects and assemblage.

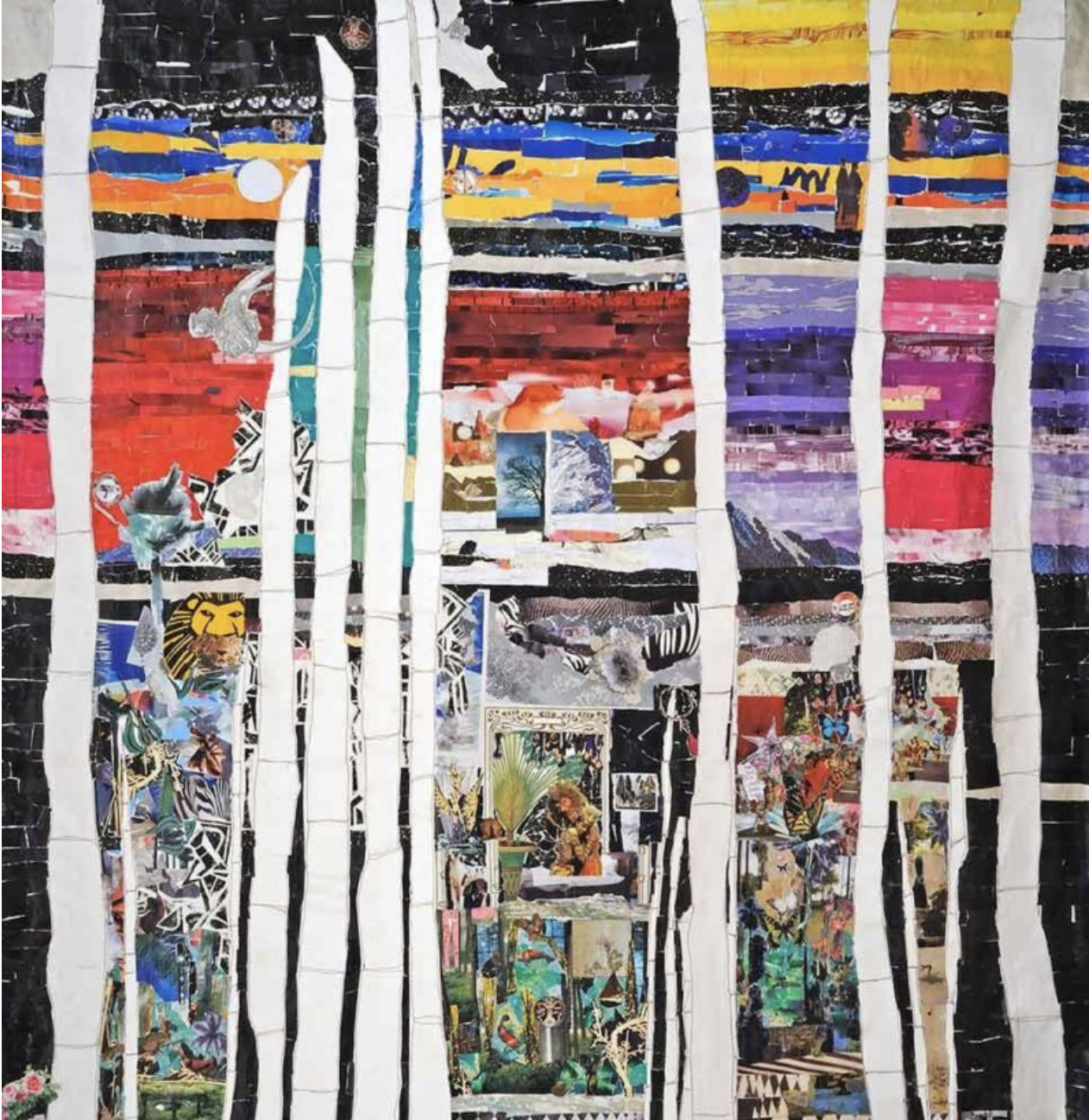

Amber Robles-Gordon, Interdimensional Realms I, 2017, paper collage on canvas, 72 × 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

N. K. Jemisin’s quote used in this title is right, and I thank her for the reminder: what we imagine and think subconsciously takes on force in our everyday lives. Maybe the multiverse is as simple as turning right instead of left at an intersection; as possibilities change, no matter how minutely, so does reality. Amber Robles-Gordon’s sculptures are rhapsodic with precision and color and function as symbolic representations of her self-examinations and how they are interwoven with gender, race, politics, geographies, and how we access deeper quantum fabrics. Working at the pivot point where painting meets the found object and assemblage, Robles-Gordon reactivates the use-value of what is considered detritus. From her perspective as an interdisciplinary artist, she says that hybridity is about intersectionality. Robles-Gordon wants her work to prompt inquiry into whose imaginaries we are living and why. Her art urges us to apprehend quickly the power of our minds, and it challenges us to rectify our relationship with accumulation by making it beholden to a rhetoric of justice and care.

—Jessica Lanay

Jessica Lanay What research or knowledge went into creating your own kind of cosmological understanding of where your work comes from?

Amber Robles-Gordon So much of my artwork is about artistic and personal practice. Art and creating are intricate parts of building, defining, and redefining who I am as a person. I really think that, innately, art became something that I rely upon. Early on, it was a method of self-reflection and support; it was a mechanism of healing, a mechanism of communicating. And because it helped centralize my thought patterns, my processing, and my categorizing of what is important to me, it then just evolved into being alongside who I am.

And does that always work every day? No. No. (laughter) ’Cause I’m human.

JL Nothing does.

ARG Exactly. It’s what keeps me centered and grounded. I don’t think that there’s an aspect of life that is not affected in some shape or form by artistic expression. I don’t think that people really understand the reach of the image, the reach of a vision, and how that can be the backbone of industries and mindsets, period. It’s creation; and depending on what form you take on, it can be innovation; it can manifest in science, sociology, architecture—in all of these various ways. Even when it comes to jobs that people think are not “artistic,” there’s the way that people take their own character and their personality and embody it in the job. And to me, not everybody can do that, whether you like what you’re doing or not. So in itself that becomes a reflection of artistic practice: how you do it, not what you do.

JL In previous interviews you have given, I sensed a tension between what seems inherent and/or socialized gender. I wanted to ask you about that tension between different ways that you’ve approached those ideas in your work.

ARG Damn, you ask some deep-ass questions. (laughter) I think that question, socialized versus inherent, is one of the most intricate and essential questions that we can ask ourselves about society. In some sense, if you’re not asking yourself either/or, then in my opinion you’re in denial. We need to be asking ourselves these things; we need to be challenging, whether you’re on the left or whether you’re on the right, challenging our notions and understandings of gender. Combing through your own social constructs. If not, you’re a part of the problem. And unfortunately, I don’t think enough of us are doing that work. I don’t think it is advantageous to land on either. To simply land on either equals continued masses of polarization and lack of self-awareness. And that’s dangerous.

Amber Robles-Gordon, Interdimensional Realms II, 2017, paper collage on canvas, 72 × 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

JL Can you also speak to the intersection of the spiritual, the personal, and the political in your works. You gracefully draw those connections.

ARG When you think about rites of passage, when you think of the various times in your life that you have gone through a series of tasks to come to some sort of benchmark and you’ve moved on to the next season of your life, I think that this is a process that people should be going through. Not to say that everybody should go through rites of passage, but everybody should be going through a rite of consciousness, an assessment of consciousness at meaningful points in your life. I do that work within myself whether it be practices that I’m doing daily, and/or readings, things like that. And it’s not always an easy process. It sucks some days. Most often I decide to take the issue to my artwork; I do the research and further analyze it from a macro perspective.

That’s literally what I did for the series Place of Breath and Birth (2020). I was looking at my own relationship to my birthplace and where my grandfather was from, which is Puerto Rico. Being a Puerto Rican, but being outside of PR and being a person of Afro descent means looking at colorism, looking at the treatment of Puerto Ricans versus other people of the outer US territories. That made me realize it’s not just about the ill treatment of Puerto Ricans. This is about anti-blackness; this is about the US government not wanting to have to deal with the ramifications of its tariffs or annexations and/or places that they’ve acquired during or for war because these places are strategic holds for a possible future warfare. Yet these are millions of people that we’re speaking of.

Amber Robles-Gordon, The Female, The Oracle, The Nurturer (Outer Circle), The One, The Source Within (Inner Circle), 2015, assemblage on canvas, 60 × 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

JL So you’ve also referred to your work as altars, and both your work and altars have the aspects of assemblage and the found object. The found object is important because it’s something being given to you. I always like to think of altars as like telephones. Since you’ve used the language, who are you listening and/or talking to?

ARG I believe in the power of the universe. There’s a church called Unity of Washington DC. It was a place of healing for me for a long time. For example, when I went through a custody battle, that church was one of the places where I would go for refuge. And I believe in ancestors; I believe in spiritual energy. I am also a sci-fi and fantasy appreciator. I even believe in the frigging multiverse. I don’t believe that it’s as superpower-driven as it’s being presented to us in some of the entertainment and media that we see. But I believe that our brains have the potential for higher power and higher understanding of ourselves and the universe; we are not connected to only portions of it.

I also think that capitalism and industrialization have created a society where we don’t have the space to do the investigation. Our personal power has been siphoned from us daily and generation through generation. And that adds up, surely. I believe in the interconnectedness of cellular energy within and outside of the ethereal. And that’s my goal: to continue to work on my connectivity and how I present myself, my ideas, and my artwork to the world.

JL

What is your definition of hybridism, and how is it informed by Black feminisms?

ARG

Hybridism is just one of the ways I was able to understand how I relate to the world and how the world perceives me. Growing up in Arlington, Virginia, as an Afro-Latina: too Black for the white people, too white for the Black people, in between for everybody else. Then puberty hits and the perception shifts—again. Re-contextualization—again. Hybridism, Womanism, Black Feminism, Intersectionality, and Humanist beliefs are methods of self-categorization. In a society structured around labels and categories, these concepts have allowed me to further claim ownership of myself without others infringing their thoughts or their limitations on me.

Amber Robles-Gordon, The Male, The Architect, The Protector (Outer Circle), The Universe (Inner Circle), 2015, 60 × 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

JL What inspired the expansion from painting into assemblage? Your work maintains painterly qualities but with a more interdisciplinary reach.

ARG My degree is in painting, but I don’t even like painting in the traditional sense. (laughter) I paint with objects; I paint, alter, deconstruct, and then reconstruct materials. That’s what I do. And I have always been attracted to materiality first. And I’ve pushed against what I thought was traditional fine art. The vision or the ingenuity that can happen when you are tackling a new medium, that’s always been exciting to me.

JL The aspect of the found and recycling in your work has a metaphysical quality to it. How are they connected?

ARG Alma Thomas is one of my first loves when it comes to art. And Impressionism. I remember when I realized that she made a piece on a hatbox top. I was like: If she can do this, then I absolutely know that I got this. As a little girl, the Universe would present gifts to me. I collected them, picking up beads, barrettes, or colorful objects. Metaphorically, I see this as having access to other-worldly information. These interactions were teaching me how to relate and exist in the world. Additionally, I work with recycled objects to address consumerism within our society.

We are abusing the earth, endangering ourselves, animals, and plants. I try to engage in slivers of that conversation within my work. It is becoming ever so clear in our society that we are destroying our … literally our world.

Amber Robles-Gordon: The Architect and The Oracle is on view at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center in Pittsburgh until October 2.

Jessica Lanay is an art writer, poet, librettist, and short fiction writer. She is a frequent contributor to BOMB where she has interviewed artists such as Howardena Pindell, El Anatsui, Shikeith, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and others. Her debut poetry collection, am●phib●ian, won the 2020 Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Prize from Broadside Lotus Press. Lanay is the co-writer of the catalogue for the Warhol Museum’s exhibition Fantasy America. She is also the current Literary Curator for the August Wilson African American Cultural Center and the host of the digital program LIT Friday where she has interviewed artists such as Dr. Fahamou Pecou, Vanessa German, and others. For more information visit lanay.me.